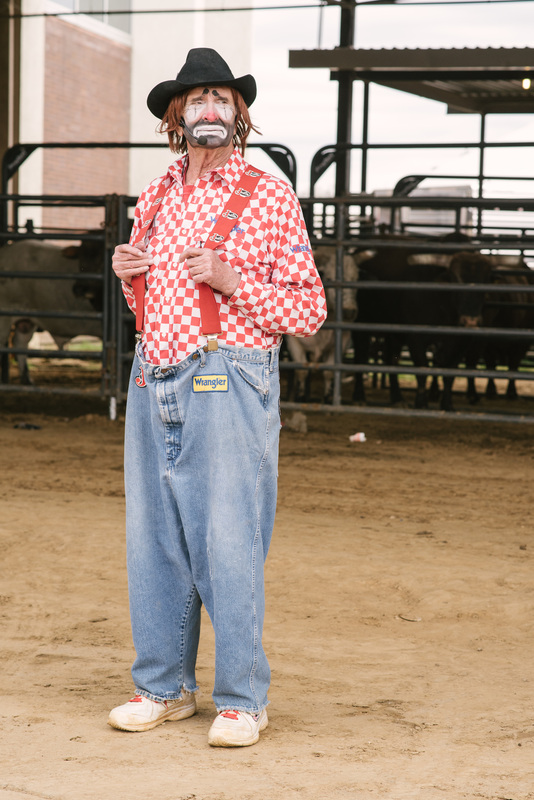

Today, we are thrilled to feature one of Dixie National's most beloved characters, Lecile.

“When I return home from trips, I have a ‘honeydo’ list a mile long,” laughs Lecile Harris in a warm, comforting voice. He has kind, sparkling eyes and a deep dimple in his left cheek. The passionately creative man, now eighty-years-old, has been a legend in the world of rodeo for over sixty years. A renowned clown and bull fighter, Harris has just returned to his home in Collierville, Tennessee, from a weekend of dazzling crowds and saving cowboys.

In 1936, Harris was born in a sleepy Delta town, nestled along the Mighty Mississippi. “I was born in Lake Cormorant, Mississippi. The town had one store, a general mercantile with a post office inside.” He laughs, “And that’s where I was born – in the back room of a mercantile store.”

Creativity surges through Harris’s veins. Even as a young child, he had a deep appreciation for the arts. “I was raised on a farm and chopped cotton. I knew there was something easier than that! I wanted to come out of there with something,” he says. Harris was a talented musician, drawer and painter, a born entertainer and brilliant comedian. In his best-selling book, Lecile: This Ain’t My First Rodeo, he writes, “{Comedian} Boob Brasfield was my first introduction to comedy….Boob’s timing was what made him so good. Even at ten years old, I recognized the importance of timing and it never left me. Just like in music, timing is everything in comedy.”

Harris started a rock n’ roll band in high school and was a star football player. “The first comedy I ever did was a bit called ‘Serenade to Insomniac.’” Harris played the insomniac. “They wanted me to go out and have trouble sleeping, but that wasn’t good enough for me,” he reflects. Instead, he poured a glass of cold milk from a refrigerator, and pretended to slam his finger over and over in the door. The audience went crazy. “I just had to overdo it to be even funnier, and I’ve kept that up throughout my clowning career.”

As a senior in high school, Harris was awarded a football scholarship to the University of Tennessee Martin. He was looking for something to keep him in shape over the summer, and heard of a rodeo across the river in Arlington, Tenn. A short trip and five dollars later, the eighteen-year-old became enamored with bull fighting and decided to give it a shot. He was hooked (in more ways than one.) “That sucker reared up and tore my shirt off and skinned my back up, and that just really made me mad,” Harris laughs.

He continued to fight bulls and began studying the rodeo clowns. “One Sunday the clown’s car broke down and he didn’t make it. I took his place. I knew nothing about it, other than watching him. I was unorthodox and very different. Because of that, it became a marketing tool for me. I reverted back to watching my favorite childhood comedians – Laurel and Hardy, W.C. Fields, and Red Skelton.” He closely studied a famous circus clown with the Ringling Brothers, who used pantomime and body language. “Back then, we didn’t have microphones. I might be over 65 yards from the crowd. It called for a lot of body language.” His physical comedy regularly had the audience roaring in laughter.

Harris’ musicality catapulted his clown career, as Harris danced with the bulls. “When the sound guy started my record playing, I’d pair off with a bull and actually dance with him. If the bull was good and hot and really rank, he’d watch my moves and match them in rhythm to the music. Every once in a while, right in the middle of the song, he’d blow towards me. When he did, I’d make a pass and step back out and start dancing again. I did that for over thirty years, and it got to be a feature.”

Harris says he loves creating a character – not for himself, but for the clown. “Lecile the clown is a different character from who I am.” Harris owned a sign company for fifty years and was an incredible artist. “I could draw, so I would draw my rodeo character. I had blueprints of acts that I did. I would draw myself in this situation to see what it was going to look like from the crowd’s point of view.” As soon as Harris steps into the rodeo arena, he becomes the clown. “When I step in, my voice inflections change, my walk changes and my vocabulary changes. I am that character until I walk out of the arena.”

Though he now resides in Collierville, the legend says, “Mississippi is just home. I’m two miles from the Mississippi line now. I didn’t get very far into Tennessee. The Dixie National Rodeo in Jackson is kind of like going home.” He smiles, “I see people in the stands who I have seen for years and I talk to them after the rodeo. So many people will say, ‘My granddaddy used to bring me to the rodeo just to see you.’ For me to be able to say that I’ve worked in front of that many generations is truly unbelievable. I have a connection with them and they have a connection with me.”

For over sixty years, Harris has captivated rodeo crowds across the world, from Arkansas to South Africa. He has been named “Pro-Rodeo’s Clown of the Year” four times and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2007. “That is certainly the highest honor. It’s your peers who put you there; not the public. It’s your announcers, other acts and even other clowns. That’s what makes it so special.”

His beloved wife, Ethel, has been his constant companion since they married shortly after college. “My wife has always supported me. She didn’t really have a choice. When she complained about me being broken up, crippled, or gone, I say, ‘I was doing this when we got married,’” he laughs. Harris and Ethel have three children, who inherited his joy for the arts. Matt, his eldest son, joined Harris in his clown acts. His son, Chuck, is a professional drummer, and daughter Christi was a dancer with The Beach Boys. To his grandchildren and great-grandchildren, he is affectionately known as “Big Daddy.”

“I was really busy all of my life,” reflects Harris. “And to this day, I remain busy. Collierville has a historical district and their signs are hand-painted the old-fashioned way. So, this morning at 5:30am, I was up on the square lettering signs for the city. Painting is still kind of my therapy.” Harris continues performing in rodeos most weekends of the year. “I fought bulls for thirty-six years, had a lot of broken bones and licks. I have an old tractor that hasn’t been used in ages and is completely rusted down.” He laughs, “That’s just the way I’m going to be if I give up. I still enjoy what I do, and when I don’t enjoy it, I’ll just walk away.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed